Before going to bed last night I checked my email and spam folders. Since migrating my website and email to a new hosting company last month, more robust email filtration has thankfully had more spam, but also some important emails, like a few from my students, going straight to the trash. Sure enough, it wasn't a student's email I found in the junk bin this time, but one from the folks at Baker's Violin Rosin.

I'd first heard about them in 2014, in either the Facebook Violinists group or on violinist.com. Apparently, they are among the few companies still making rosin the way it traditionally was made - with sap (or colophony) harvested from living trees and "distilled in solid copper vessels over open fire pits" using recipes that date back to Paganini. Unfortunately, it turned out that you couldn't just order some from their site, Shar music, or Amazon. Their rosin is only sold fresh through their email members list and is in high demand. Furthermore, their trees can only be tapped seasonally. The exclusivity and word-of-mouth approach added to the intrigue.

So I added my email to their list, not sure if anything would ever come of it, and every so often I'd wonder if my turn to order rosin would ever come. A couple years went by, then finally in 2016 I received the mythic email - I had 48 hours to reply and I could order two rosin cakes max. I decided to go with one of each of the blends they make - the Original and the Vuillaume Citron. I haven't even considered using a different brand since those two little tins showed up in the mail. I've enjoyed both at different times - the Original for its subtle warmth and richness, the Citron for its brilliance and clarity. The smell of a sweet pine forest that wafts through the air every time I rosin up adds to the magic.

In any case, no other chances to order came my way until last night, and I've coveted these cakes these past few years and as they've shrunk and dried out. Once I find the best, I'll ration, mend, or repair as much as needed to avoid having to settle with "second fiddle." I recently started wondering if I'd ever get the chance to order more rosin. Thankfully, the Baker family seems to be right on schedule with me. I quickly ordered my two cakes before falling asleep and dreaming about a terrible scenario where I couldn't get any new strings and had to string my violin with wire from the hardware store! The sound was terrible!

Hopefully there won't be any string shortages in the new year and my new Baker's rosin will avoid the mail headaches that seem to be going around lately, but the question remains - can a rosin really make your instrument sound better? What else can we do to improve the tone, balance, and projection of our violin, viola, or cello?

Let's be clear, assuming you have solid instruction, nothing will make you sound better then your regular, focused practice time. Beyond this, while those $59 violins demo-ed on YouTube can sound decent in the hands of a virtuoso, they will never match the quality of the ones these artists perform on, usually costing hundreds of thousands if not millions of dollars and often loaned to them by wealthy benefactors. The depth of tone and character an instrument possesses are not always tied to price, but price generally does reflect quality in the violin market. Please see my recent post here for more on the topic of purchasing a decent instrument.

Beyond the player and the instrument, we have a number of factors that can improve the sound of our violin, viola, or cello:

- the setup

- the bow

- the strings

- the rosin

- the tailpiece

- the accessories

The setup: For the purpose of enhancing tone quality, this includes primarily the soundpost and bridge. When either is out of place or tilting, reverberations are not going to transfer and mature inside the instrument body effectively. While the soundpost should be checked by a luthier every few years, the bridge can be adjusted easily and should be checked often.

The bridge should align with the fingerboard so that the G and E strings are spaced equally from its edge and the feet of the bridge should be roughly centered between the divots of the F-holes. Over time the bridge will leave faint marks in the varnish, making it easy to notice when it has shifted out of place. This type of shifting is uncommon unless the strings have gotten very loose or the instrument has taken a tumble.

A tilting bridge is very common however. When viewed from the side of the instrument, make sure that the back edge of the bridge is parallel to the corner of the C-bout, or in other words, making a right/90 degree angle to the belly.

If the bridge is tilting (usually toward the fingerboard), for violins and violas, rest the instrument in your lap with the scroll pointing away from you. Using the index and thumb of each hand, pinch the bridge between the G and D strings, and the A and E strings respectively, and gently glide the bridge into position. It is not necessary to loosen the strings. Loosening them would actually make your repositioning pointless as it's usually tuning the strings up to pitch that causes the bridge to tilt in the first place. However, the bridge is under incredible pressure so move slowly, stopping to check the alignment, and trying again as needed.

It is quite difficult to move a cello bridge without loosening the strings. Still, all the other alignment principles apply and you should loosen the strings just enough to move the bridge. Being taller, cello bridges seem to be more susceptible to warping over time, so it's especially important to check their alignment frequently.

Finally, it's worth mentioning that the playability of the instrument, while not affecting the tone directly, does have an impact. If the strings are too high (the "action"), the pegs are stuck, the fingerboard is warn and pitted, or the fine tuners rattle, intonation will be a challenge and it will be hard to create beautiful melodies with all the struggle going on behind the scenes.

The bow: All too often our choice of bow is an afterthought. As your primary tool of tone it really shouldn't be. A nine-year-old student needed to move up to a bigger violin recently. He visited his local shop and came back with a couple of instruments to show me, remarking that he liked one of them better, but only with one of the bows. Sure enough, the other bow made the violin sound scratchy and dull. Bows in fact have their own tone, which can either enhance or detract from the sound of your instrument. My recommendation is to always find the instrument you like and then find a bow that will bring out it's best qualities, or perhaps balance the qualities you wish it had more of.

The strings: Steel, synthetic, composite, gut? Gold, platinum, chrome, silver, aluminum? So many different materials go into making strings we assume there must be tonal differences. However, many string sets are expensive, deterring students who would otherwise enjoy experimentation. While it's impossible to determine which type of string will work well on a given violin, viola, or cello without trying some out, the overall string type and brand can give us clues.

In general, steel core strings have the longest lifespan and the brightest, most direct and responsive sound. They settle in quickly, are often the cheapest strings available, and while often a favorite among fiddlers who might need to play over a rowdy band, most Classical violinists graduate from steel strings early on in the search for more warmth and complexity. Many cellists on the other hand, prefer steel strings such as Larsen and Jargar however, needing that focus and volume to cut though and project within an orchestra or ensemble.

On the opposite end of the string spectrum are gut strings. Among the more expensive choices, they can sound rich and warm, but are slower to respond and harder to keep in tune. They can work very well on some instruments however, and players focusing on historical accuracy often favor them.

Synthetic and composite strings are newer innovations (newer being a relative term of course), with the goal of creating the tonal richness of gut strings with the responsiveness and stability of steel strings. These strings have a metal winding and a man-made core material, the most common synthetic strings being Thomastik Dominant. Except beginners and fiddlers, most violinists and violists these days use synthetic or composite strings. Each brand and type offers a spectrum of tone colors, ranging from brighter and louder, to darker and warmer. Here are a few popular composite string sets and their qualities:

- Thomastik Dominant (available across the violin family): focused and stable, a favorite of violinists for nearly 50 years.

- Thomastik Infeld Red and Blue (violin only): Red = a warmer tone to balance bright violins. Blue = a brighter tone, to balance darker violins.

- Pirastro Tonica (violin and viola): similar to Thomastik Dominant, but without the metallic edge and often better priced.

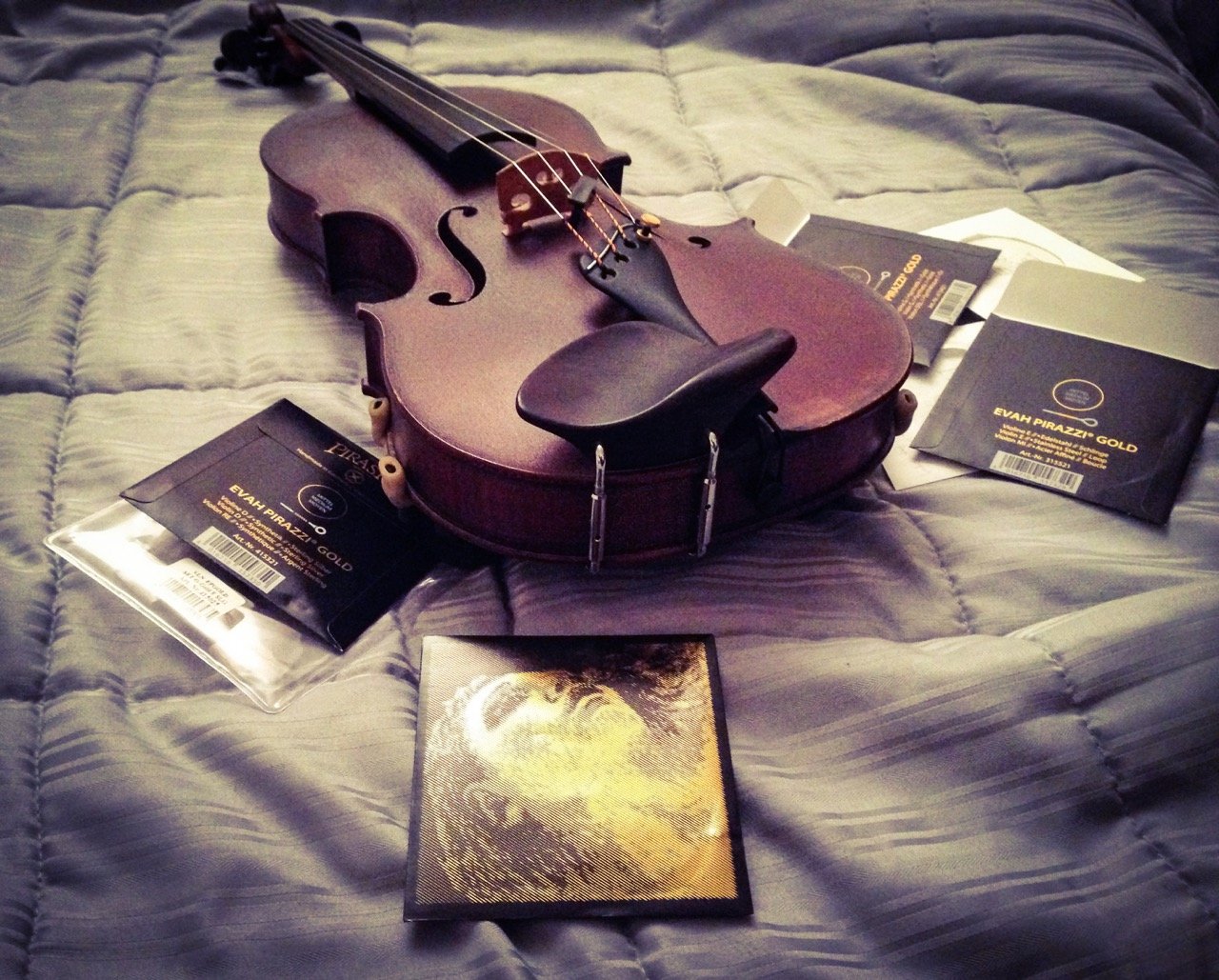

- Pirastro Evah Pirazzi (available across the violin family): a high tension composite string with excellent projection and a bright tone, a favorite among soloists.

- Pirastro Evah Gold (available across the violin family): warmer and more nuanced than the Evah Pirazzi, but still with good projection and focus.

- Pirastro Obligato (available across the violin family): gut-like and even a bit warmer than the Evah Gold.

Through the sponsorship I enjoy with Pirastro I've been able to try most of their string types at this point, and through my work with Strings magazine over the years I've also tried many of the sets by Thomastik, D'Addario, and Larsen.

Evah Golds have been my go-to strings for nearly a decade, but a newer Pirastro set I'm intrigued by is their Perpetual. I didn't end up liking it as much as the Evah Golds on my violin and took them off after a few days, but I've had them on my viola for a couple months now and have enjoyed the depth and focus they've added. I have a set of Evah Golds waiting in the wings, and it'll be interesting to see how I feel about them when I've worn out the Perpetual.

Another string set I found particularly interesting to try on my violin were Thomastik Peter Infeld (PI) strings. I had the sense I was hearing overtones/undertones I didn't normally hear. The effect was subtle, and ultimately too different to keep using the strings, but intriguing.

Finally, in my search for high quality yet affordable strings for my violin and viola students, I've been very impressed by Warchal. I've tried a few of their sets myself and found them comparable to Thomastik and Pirastro - Karneol (similar to Pirastro Obligato or Infeld Red), Brilliant (similar to Pirastro Evah Pirazzi or Infeld Blue), Ametyst (similar to Pirastro Eva Gold or Thomastik Dominant).

For more about strings, Quinn Violins has a wonderful page here. As a company they also offer custom sets and competitive pricing. I'm not affiliated with them, but I appreciate the time they've taken to write about each type of string and educate their customers.

The Rosin: Circling back to rosin, we have different colors and compositions which can indeed affect the tone of your instrument.

The three main rosin types are light (yellowish), amber (orange/red), and dark (often nearly black). Lighter rosin tends to be harder, while darker rosin tends to be softer and stickier. Lighter rosin tends to be brighter sounding, while darker rosin tends to be warmer sounding. In general, violinists tend to gravitate towards lighter rosins while cellists tend to prefer darker rosins, with viola players falling somewhere in between. Players living in warmer, more humid climates may also like lighter rosins, while players in colder and/or dryer climates may prefer darker rosin. Finally, players who tend to be more heavy handed may do better with a lighter rosin, while players who need more grip on the strings may prefer a darker variety.

Some rosins contain additives like gold and silver, reported to enhance the sound. Other makers, like Leatherwood Bespoke Rosin, offer customized blends said to bring out certain qualities.

Like strings, rosin choice is individual. While we can use these generalizations as clues, it's impossible to know what will work best for a certain instrument and player until we try. As a child I used Hill Dark rosin for years, likely because I tended to have a lighter touch and my teachers and conductors were always telling me to "play out more." I eventually moved on to try a variety of Pirastro rosins and Andrea Solo Violin rosin. For folks with allergies, Jade rosin is a good hypoallergenic choice. I've also heard positive reviews for Magic Rosin.

The Tailpiece: While tailpieces may seem purely functional, or perhaps decorative when it comes to those with inlays, in my 2012 Violin Geek Podcast interview with Nicolas Frirsz I learned all about the tonal contributions of the tailpiece - including the possibility of improved clarity, more richness in the lower end, the elimination of wolf tones, and an overall better resonance. I've used one on my violin for the past decade and more recently also on my viola and cello, and can say that all of those qualities have been my personal experience.

In general, while most of the vibrations travel down the bridge and into the belly and body of a violin family instrument when we pluck or bow a string, some do travel to other places, setting off harmonics and overtones that can either be pleasing or detrimental to our overall sound. While not as obvious a difference as the type of strings used, or maybe even the rosin, the composition and weight of any tailpiece will make a difference in tone. While Frirsz tailpieces aren't the only innovative tailpieces out there, their signature graduated lyre design gives the bass strings more length behind the bridge, and thus, more string length to vibrate for increased resonance. I am also not affiliated with Frirsz music, but continue to enjoy his tailpieces on my instruments.

The Accessories: Finally, for violins and violas, our choice of chin and shoulder support, and for all bowed strings, any additional components, like an installed pickup, can affect our tone. Overly bulky or heavy pads, especially those that touch the back of the instrument can dampen the sound, as can the clamps of chin rests and 1/4 inch pickup cables.

Match One and Pirastro, among others, offer shoulder rests made of wood which are said to help enhance the resonance. Proponents of playing without a shoulder rest cite, among other things, the ability of a player's body to act as a secondary resonance chamber, improving tone. At the end of the day, these gains are among the more subtle, so choosing comfort over the possibility of improving tone in these departments makes the most sense to me.

I hope this has been a helpful overview of the many elements that affect a violin, viola, or cello's tone, and hopefully gives new options to consider if you're not 100% happy with your sound, yet not ready to step up to a better instrument just yet.

Happy Practicing!